Saskatchewan's Alvars

Hidden in Plain Sight

Alvar is a globally imperiled and unusual group of calcareous habitats characterised by shallow mineral soils over limestone or dolomite bedrock, a natural lack of trees, abundant rare species populations, and an unusual prairie-like plant community. It occurs in only five countries worldwide. In Canada, almost all known alvar is found in the Great Lakes Basin in Ontario, though it is also known from Manitoba, Quebec, Newfoundland, and the Northwest Territories.

Last year, while acting as the Botanist for the Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre, I set out to find out whether alvar existed in Saskatchewan. It had never been found there before, and few people familiar with the habitat would have expected it to be — limestone and dolomite bedrock are quite uncommon in Saskatchewan, and much of the area where alvar could occur is very remote and densely covered with boreal forest, making access extremely challenging.

Nonetheless, my prior work in Saskatchewan had left me with a strong sense that there was still much to discover there, so I spent several weeks flagging possible alvar clearings using remote sensing. Because alvar patches can appear extremely similar to boreal wetlands and no predictive method exists yet to identify them, I focused on areas with known or modeled limestone/dolomite bedrock, since these are essential pre-conditions for alvar. I excluded boreal wetlands by only selecting clearings that had no apparent hydrological context which could suggest that they were boreal bogs or fens. I also used the presence of trees growing in unusually straight lines to select target sites, as limestone and dolomite tend to fracture in long, straight cracks and trees confined only to these cracks suggest that soils are shallow — another diagnostic feature of an alvar.

Finally, after weeks of planning, my long-suffering girlfriend Sabina and I were dropped off by boat at a remote lake several hours southwest of Flin Flon, where we began our hike. I felt that the odds of successfully finding alvar in Saskatchewan were so low that the first expedition had to happen the hard way, on foot.

A full backpack, prepared and ready with camping and sampling gear.

A full backpack, prepared and ready with camping and sampling gear.

The local mosquitoes were lively company. Their incessant drone against the tent fabric was annoying, but not as bad as going out into them.

The local mosquitoes were lively company. Their incessant drone against the tent fabric was annoying, but not as bad as going out into them.

After two days of bushwhacking to reach the first suspected site, we broke out of the boreal forest into the first clearing. It is a remarkably surreal feeling to walk out of the buggy northern boreal forest into a broad, grassy clearing dominated by wildflowers and dotted with prairie onions and wild chives. It is like being instantly transported somewhere completely different, and very far away from where you actually stand.

There was soon no doubt that the clearings were indeed alvar, after checking the soil profile and looking closely at the plant community (see the next page for photos of several indicator species). What might easily have been mistaken for just another wetland from the air was in fact solid ground, and a new habitat for Saskatchewan — likely the rarest in the province.

A photo of an alvar soil profile from the Limestone Lake site, showing the very shallow depth to the underlying bedrock and the strongly light coloured mineral soil profile.

A photo of an alvar soil profile from the Limestone Lake site, showing the very shallow depth to the underlying bedrock and the strongly light coloured mineral soil profile.

The Limestone Lake alvar, showing the resemblance to a boreal wetland that has probably helped it escape notice for so long. Although the surface is wet, a helicopter may easily land on it.

The Limestone Lake alvar, showing the resemblance to a boreal wetland that has probably helped it escape notice for so long. Although the surface is wet, a helicopter may easily land on it.

Orobanche fasciculata, the 'clustered broomrape', is a compelling alvar indicator species because its habitat is prairie and it parasitises Artemisia (sagebrush) shrubs which are also prairie indicator species.

Orobanche fasciculata, the 'clustered broomrape', is a compelling alvar indicator species because its habitat is prairie and it parasitises Artemisia (sagebrush) shrubs which are also prairie indicator species.

Allium schoenoprasum, wild chives, is an obligate prairie/alvar species that does not occur in the boreal forest. Here, incredibly, they cover the ground so densely they are the dominant species.

Allium schoenoprasum, wild chives, is an obligate prairie/alvar species that does not occur in the boreal forest. Here, incredibly, they cover the ground so densely they are the dominant species.

Solidago ptarmicoides, the 'upland goldenrod', requires mineral soils. It is widespread in alvars and prairies in Eastern Canada, but this may be the most northwesterly population in North America.

Solidago ptarmicoides, the 'upland goldenrod', requires mineral soils. It is widespread in alvars and prairies in Eastern Canada, but this may be the most northwesterly population in North America.

Allium stellatum, the pink prairie onion, is as diagnostic for prairie/alvar as its name suggests.

Allium stellatum, the pink prairie onion, is as diagnostic for prairie/alvar as its name suggests.

'Blue-Eyed Grass' is a common species of native prairie grassland.

'Blue-Eyed Grass' is a common species of native prairie grassland.

Dodecatheon pulchellum, the 'saline shooting star', is one of the most distinctive and beautiful of the alvar wildflowers.

Dodecatheon pulchellum, the 'saline shooting star', is one of the most distinctive and beautiful of the alvar wildflowers.

A field of shooting stars at the first site.

A field of shooting stars at the first site.

Above and beyond the rarity of the habitat itself, surveys at Saskatchewan's alvars ultimately confirmed extraordinarily high levels of rare species diversity, including at least five new species and one new genus to Saskatchewan. Nearly 45% of the species identified in 2020 are rare species or new species to the province, underscoring the extremely high conservation value of the sites.

Several species discoveries were particularly exciting, including Cypripedium reginae, the ‘showy ladyslipper’, which was found at the Limestone Lake site. This population is only the third known site in the province and an apparent rediscovery of the species, as it was thought to be extirpated from Saskatchewan. Two populations of Asplenium viride, the 'green spleenwort', represent the first records of the genus for Saskatchewan and apparently the first records of the species between the Alberta Rockies and the Great Lakes. Dermatocarpon dolomiticum, an unobtrusive but very unusual lichen species, is federally critically imperiled and the new population is something like 1,600 kms from the closest sites in the Great Lakes basin. And Botrychium tenebrosum, the ‘swamp moonwort’, is a new species of these enigmatic and rare ferns for Saskatchewan.

These findings only represent approximately three days of surveys, suggesting that further work will almost certainly uncover many more exciting findings.

Aerial overview of one of the alvar patches near Limestone Lake, showing the slightly elevated occurrence on a dolomite plateau above the surrounding landscape, as well as the very striking criss-cross pattern of trees growing in lines indicating the shallow soils of the clearing.

Aerial overview of one of the alvar patches near Limestone Lake, showing the slightly elevated occurrence on a dolomite plateau above the surrounding landscape, as well as the very striking criss-cross pattern of trees growing in lines indicating the shallow soils of the clearing.

Cypripedium reginae, the 'showy ladyslipper', unfortunately was well past prime flowering by the time it was photographed, but it is one of the most surprising species observed at the alvars - the first SK sighting in nearly thirty years.

Cypripedium reginae, the 'showy ladyslipper', unfortunately was well past prime flowering by the time it was photographed, but it is one of the most surprising species observed at the alvars - the first SK sighting in nearly thirty years.

Asplenium viride, the 'green spleenwort', is an extremely unusual fern species, and a new genus for SK.

Asplenium viride, the 'green spleenwort', is an extremely unusual fern species, and a new genus for SK.

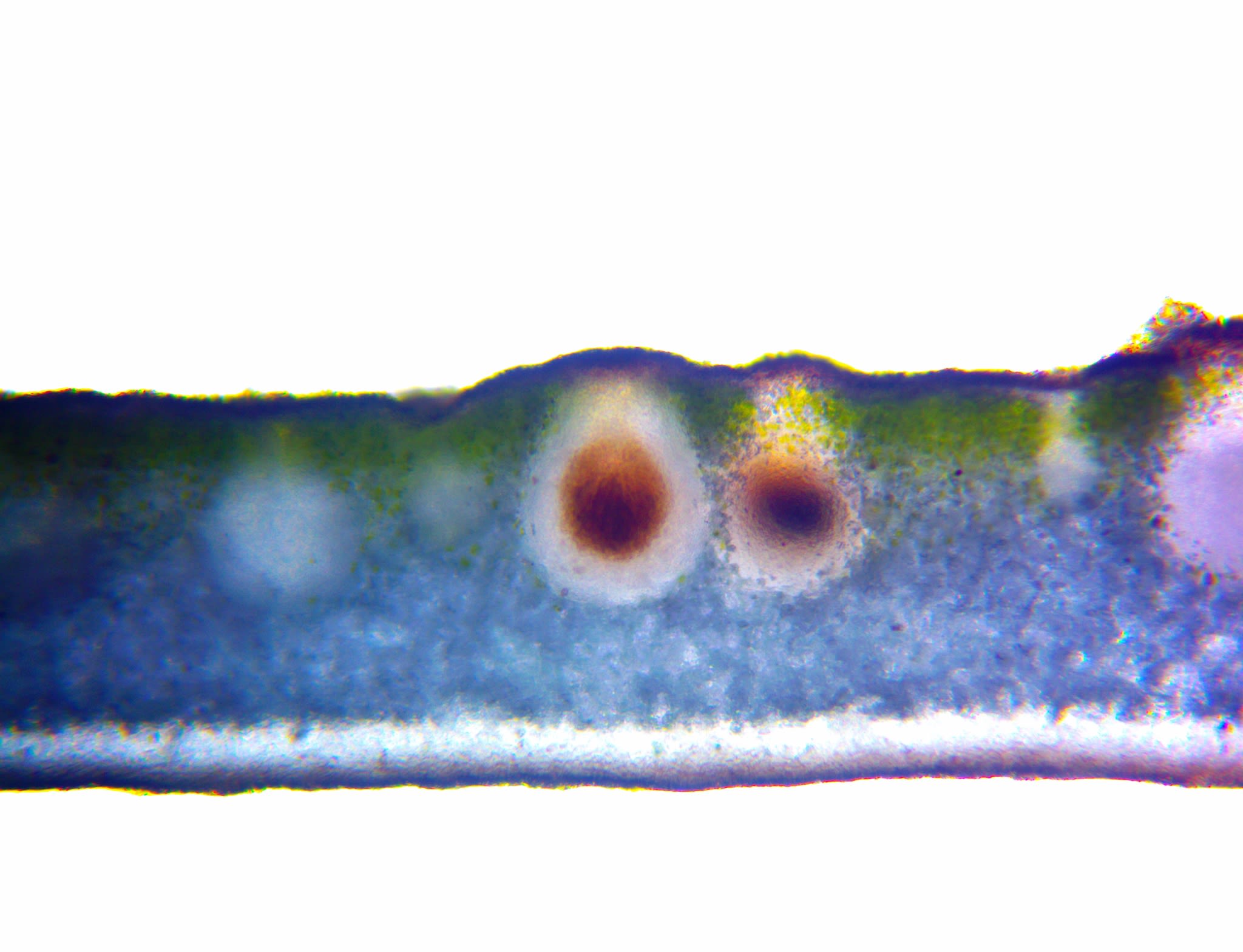

Dermatocarpon dolomiticum, the 'limestone stippleback lichen', is an unobtrusive lichen found on rocks underwater at seasonal pools at the Limestone Lake site. The reproductive structures are the tiny black dots on the surface that give the lichen its common name.

Dermatocarpon dolomiticum, the 'limestone stippleback lichen', is an unobtrusive lichen found on rocks underwater at seasonal pools at the Limestone Lake site. The reproductive structures are the tiny black dots on the surface that give the lichen its common name.

A microscope photo of Dermatocarpon dolomiticum, showing the reproductive structures shaped like tiny embedded flasks (perithecia) that release the spores.

A microscope photo of Dermatocarpon dolomiticum, showing the reproductive structures shaped like tiny embedded flasks (perithecia) that release the spores.

After confirming the first site, I felt justified in requesting the use of a wildfire helicopter to visit two more clusters of predicted alvar, confirming them and documenting what is likely the most substantial 'pavement' alvar in Saskatchewan, near Cumberland Lake (below). This broad, flat area of bare dolomite bedrock is dominated by nonvascular species (mosses & lichens) with wild columbine flowers confined to the cracks. The area transitions into a limestone woodland, which is similar to an alvar but with higher tree canopy cover.

A pavement alvar, featuring a broad slab of flat, bare dolomite bedrock with a community dominated by mosses, lichens, creeping juniper, and wildflowers.

A pavement alvar, featuring a broad slab of flat, bare dolomite bedrock with a community dominated by mosses, lichens, creeping juniper, and wildflowers.

The largest pavement alvar discovered in Saskatchewan near Cumberland Lake.

The largest pavement alvar discovered in Saskatchewan near Cumberland Lake.

Although the total area of alvar in Saskatchewan is small (with fewer than a hundred hectares in the whole province), the biodiversity found there is spectacular, and the finding prompts many questions – How much more alvar remains to be found in Canada’s remote boreal? Does Alberta also host alvars? What role are these remote boreal alvars playing in the dispersal and population genetics of the rare species they host so far away from the Great Lakes? For now, these questions will remain mostly unanswered, but one thing is clear – a predictive model of alvar distribution in the boreal is profoundly needed. If Saskatchewan’s alvars have been overlooked for so many decades, where else do they await discovery?

Another alvar patch at the Cumberland Lake site, showing lines of creeping vegetation and vernal pools of standing water which support the unique plant communities found at the site.

Another alvar patch at the Cumberland Lake site, showing lines of creeping vegetation and vernal pools of standing water which support the unique plant communities found at the site.

But the most important question is — what comes next for these sites? Obviously, they are exceptional— the global rarity of the habitat, the abundance of rare species and new species to Saskatchewan, the extremely small area of alvar in Saskatchewan, and the complete lack of invasive plant species make this abundantly clear. They are objectively deserving of the highest class of protected area in Saskatchewan — an Ecological Reserve.

Flying out of an alvar clearing, showing the rapid transition back to the boreal forest and the surrounding wetland-dominated landscape.

Flying out of an alvar clearing, showing the rapid transition back to the boreal forest and the surrounding wetland-dominated landscape.

Unfortunately, however, all of the newly discovered alvars fall within an 'incentivised exploration area', wherein the province of Saskatchewan subsidises resource exploration by mining companies. Readers who wish to lend their voices to the conservation of Saskatchewan's alvars are encouraged to contact the Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Energy and Resources and support the permanent and complete protection of these unique and irreplaceable examples of Saskatchewan's biodiversity.

My term at the SKCDC ended at the end of March, 2021, and all views expressed here are solely in my capacity as a private individual and conservationist.

Acknowledgements:

- The Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment, for their support with the fieldwork that documented the alvars and their biodiversity.

- Jeff Keith, of the SKCDC.

- Sabina Hamilton and Jillian Kusch, for accompanying me into the Limestone Lake and Cumberland Lake alvars, respectively.

- Dr. Richard Caners of the Royal Alberta Museum for his patient mentorship and assistance with bryophyte IDs.

- Dr. Othmar Breuss, Vienna, for assisting with the identification of D. dolomiticum.

- Ben Sawa, of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment, for contributing Protected Areas funding that made field visits possible.

- Nature Saskatchewan, which provides funding for SKCDC positions.

- Bob Spracklin, aviation coordinator, for arranging the helicopter flights to the second and third alvar clusters.

- Ben, Nolan, and the other Conservation Officers at the Denare Beach office for their invaluable assistance with the fieldwork.

An article about the remote Yukon research camp, 'Pika Camp', and the climate change work I assisted with there.

An article about the remote Yukon research camp, 'Pika Camp', and the climate change work I assisted with there.

An article about Alberta's endangered five needle pines and the work being done to save them from extinction.

An article about Alberta's endangered five needle pines and the work being done to save them from extinction.